Spoiler-free zone until the “THE ENDING” heading.

ANALYSIS

Stories where the protagonist is absolutely, head-over-heels obsessed with a particular person are fascinating to me. My Letterbox’d “Likes” feature movies like Ingrid Goes West, Single White Female, and The Crush. After some void opens up in their life, the protagonist fills that void with the personification of the ideal that they’ve lost. In Ingrid Goes West, for example, Ingrid loses her mother. She considered her mother to be her best friend, and that feeling of friendship was taken away from her. To get it back, she stalks and pursues other women in the hopes of re-gaining that same friendship with someone else. Loss followed by desire is a typical formula for obsession movies.

In Saltburn, Oliver doesn’t exactly start from a place of loss at the very beginning. His backstory doesn’t involve the universe cruelly ripping away a loved one or plunging him into crisis. He starts off on an apparently good enough foot: he is attending Oxford, and although he isn’t flourishing right away, he isn’t irredeemably dysfunctional. He is grasping for something he thinks he would love to have, rather than trying to capture some specific feeling he’s lost. This psychological impulse leaves us with a character whose drive is mercilessly and disgustingly strong, but whose goals seem unclear to those who don’t identify with his compulsion to seek much more than he truly needs. This is not a story about a protagonist starting from the bottom and fighting their way to the top. This is a story about a protagonist who loves to “want” things. It doesn’t really matter what those things are - he’ll try to gain access to them anyway.

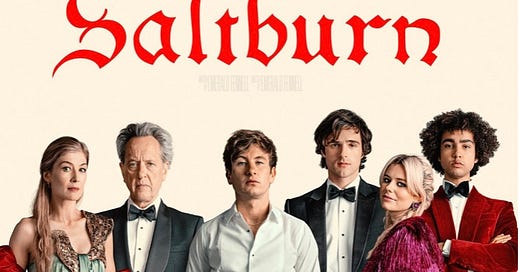

I didn’t realize until the end of the movie that this was created by the same woman who wrote Promising Young Woman. Emerald Fennell is uniquely talented at inducing a feeling of hopelessness and futility in the viewer. On one hand, it makes me reflexively dislike the story in a “How dare you make me feel like this?” way. On the other hand, I do have to give her credit for not shying away from the brutality of emotion that comes when your actions are motivated by revenge (like in Promising Young Woman) or by envy, like in this film. She depicts these as bottom-of-the-barrel, filthy emotions whose consequences unnerve us. This seems about right to me. Envy is a mix of two boundlessly powerful emotions: love and hate. Anyone who has been deep in the throes of envy knows just how ruthless your thoughts can become. Emerald Fennell personified those thoughts in the character of Oliver, and let him perform action upon envious action without encountering much resistance.

This has been framed and marketed as an “Eat the Rich” film, but that doesn’t seem to be the message that Fennell is most interested in capturing. The estate acts more as a reflective backdrop for the events of the story. Even the average person who has enough resources to keep up a decent lifestyle can look at the sprawling estate and understand why Oliver would “want in.” Showing the audience this visual bounty puts us in Oliver’s shoes. Both Oliver and the viewer gain access to extravagance over the course of the film. It doesn’t come off as a class critique to me. Rather, the constructed and maintained estate comes second to the real exploration: the exploration of raw human desire.

Oliver goes further than reaching for wealth. He reaches toward the ideal of social acceptance. When an awkward student latches onto Oliver at the beginning of the movie, this makes us sympathize with Oliver. No one wants to be at the bottom of the social ladder moments after starting at a new school. Meanwhile, Oliver spots Felix, who is at the top of the social ladder in every sense. He’s tall, he’s handsome, he gets whatever girl he wants, and he has money. People hang on his every word. Oliver is not at the absolute bottom of the hierarchy, but he’s in an arguably worse state: he’s completely invisible. He doesn’t matter. This invisibility is the very flaw, however, that enables him to make progress toward his ultimate goal of capturing what Felix has.

I’m reminded of the “incel” concept - do they really just “want sex” or “want a girlfriend”? On some literal and simple level, yes. But it’s more often that they’re reaching toward an ideal. Would they be happy with just any woman as their own? No. If they value beauty, they want their woman to be the most beautiful. If they value intellect, they want their woman to be the most intelligent. If they value devotion, they want their woman to lay down her life for them. Capturing their type of woman would mean that they are themselves the type of man who is worthy of her. With such a woman as their mirror, they finally see a reflection of themselves that they can be proud of. Along these lines: does Oliver simply “want a friend?” No. Oliver values social, sexual, and material abundance, which Felix embodies. He wants to be the type of man that Felix already is - a man worthy of friendship, attention, and love. That’s why his actions are so circuitous and wide-reaching. It is not enough to merely be adjacent to worthiness. Oliver needs to destroy worthiness in others, then position himself as the sole heir of that worth.

THE ENDING

Spoilers up ahead. Beware!

As with the ending of Promising Young Woman, people have varied reactions to Saltburn’s ending. Personally, I thought the reveal of Oliver’s level of involvement from day 1 was a little unnecessary. I wouldn’t say it was too contrived, but I think the story would have stood fine on its own if everything wasn’t spelled out so clearly for the audience. “Trust your audience” is popular fiction writing rule, and eschewing that rule with a villain-tells-all monologue can feel condescending to an audience. I can’t tell if Fennell intended to do this to the viewer, but I like to give writers the benefit of the doubt. Oliver’s monologue may be an extension of his character, showing that he has the impulse to explain himself and be heard. He can’t help but recite this celebratory manifesto as he completes the last step in his plan, even though the only one left to bear any witness is Felix’s mother, who is a “Schrodinger’s listener” due to her comatose state.

Some might say that the ending and his motivations are muddled. Does he want to be romantically involved with Felix? Does he want the estate? Does he want lots of friends? Does he want to be important? Does he want to get away from his old life? Does he want to fulfill his murderous urges? To me, the answer to any “Does he want…” question is “Yes. He wants.” As Oliver himself claims, he is a vampire. Vampires nourish themselves by draining others. Oliver, however, is even scarier than the average vampire. Vampires take what they need; Oliver takes what he wants. He doesn’t just drain his victims. He infiltrates their lives, annihilates everyone around them, and even violates one of their graves after death. There is no end to his wants, even after he gorges himself on the most materially and societally abundant people he has access to.

With this endless greed in mind, we have to ask: is Oliver fulfilled in the final scene? He’s dancing around, and certainly appears to be having fun. But the image of a naked man completely alone in a lavish house is representative of Oliver’s mental state. Throughout the film, we see the contrast of the raw human form against a constructed estate backdrop. We have the beautiful bathroom containing dirty bath water, a woman in a skimpy nightgown who reveals she is menstruating, a corpse in a perfectly manicured maze, and more. Oliver being at his most simple and vulnerable, dancing across the expansive house, is one last example of paradox. This final look at Oliver, where he celebrates getting what he desired, makes the viewer feel empty. What will he do now that he’s gotten everything he apparently wanted? For someone like Oliver, who is so intelligent and driven by a compulsive level of desire, it’s hard to imagine that he’ll ever be truly happy. He’s checked all the boxes off of his to-do list, but chances are, he’ll make another one soon enough. For the time being, though, as the film comes to a close, what else can he do but dance?